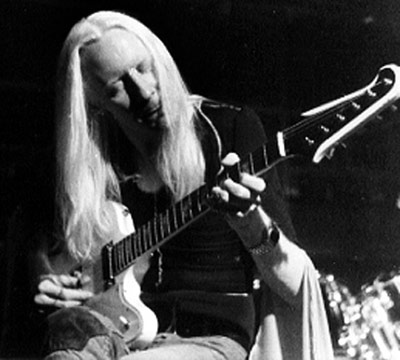

Much More Than Survival Johnny Winter's...

Zoo World - The Music Megapaper, 9 May 1974 Issue 58

Zoo World - The Music Megapaper, 9 May 1974 Issue 58

by Billy Altman

After two decades of rocking and rolling, the star concept remains the motivational force behind our music. Yet today, tastes are fragmented to such an extent that almost no performer can reach the kind of universal acceptance which once defined the star phenomenon. It now seems that the best strategy for making it is to seek out a little niche in the rock world, grab hold of a segment of the audience and try to hold on for as long as possible.

The list of rock 'n roll heroes who have managed to hold on while at the same time enticing more and more people into their camp can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Indeed, rock stardom is a tricky business. In 1968, how many of us suspected that in a few short years the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Brian Jones and Janis Joplin would be gone from the rock hierarchy? The psychedelic age of the sixties ended with a bang not a whimper, and there ain't that many around left to tell the story.

Entering the disarmingly modest apartment on Manhattan's east side, that Johnny Winter calls home, I realized that Johnny is indeed one of the few artists who has managed to make the voyage from the sixties to the seventies, and still remain a giant of the rock world.

We all know of Johnny's beginnings in Texas, and his almost instant stardom when he signed with Columbia Records. He was one of rock's first and most celebrated bonus babies, expected to go from rumor to legend in ten easy steps, and that he did. But when all the hype had settled it was on the strength of his music, of his powerful singing, frenzied guitar playing and the bearing of a true rock 'n roll soul that Johnny Winter had really made it. Yet like Hendrix, Morrison, Joplin and Jones, these qualities almost killed him. The pressures on a superstar don't readily come across to listeners and fans, because we only see what's offered on stage and we only hear what comes over the speakers. It's often hard to realize that beneath the image there's a living, thinking and feeling human being. Johnny Winter was already a star before he had to come to grips with the hard fact that endless tours and lonely motels. The strain finally took its toll and Johnny's growing dependence on drugs landed him in a hospital for almost a year.

Luckily for us though, the year away was of his own choosing, a time to seek out his own personal priorities. Now he's back with us again, and though his comeback album of last year was entitled Still Alive and Well. Johnny Winter is much more than just a rock 'n roll survivor. He's playing some of the best music of his life, capturing a new and younger audience, and perhaps more importantly he's enjoying his music and his life a whole lot more.

I asked Johnny about his meteoric rise to the top and the pressures that went with all of the instant glory.

'It was strange, really,' Johnny says, 'that we didn't even know the pressure was there. Most groups kinda build up, play clubs for awhile, then get third spot on a concert and they have time to figure out what's going on, but we really didn't. We went from doing clubs to headlining and we were so naive about it that we didn't feel much pressure. We just figured OK, we'll get up there and play. Sometimes things were just falling apart around us, we didn't know anything about playing places that big, and you can't hear much onstage, so you've gotta trust your equipment people and we'd never had any equipment people. We didn't know if we were any good or if they knew what they were doing, so we were open to anyone that came along with a good line. I mean we had the worst losers working for us for about two years and I don't know how we did it, but things just kinda came together on the job. We would have our friends tell us, you know, 'this sounds terrible' or 'this guy's asleep at the board,' and after a lot of gigs we finally got it together. But in those days it was really a lot less planned, it was the psychedelic druggie days and everyone was flowing with whatever was happening, so it wasn't that difficult for us to make things go. Looking back, I can't believe how we pulled it off.'

I asked Johnny what he thought about all the hype and publicity that was showered on him. 'Well, I had been working hard for about twenty-five years trying to get people to pay attention to me, and when they started writing all those great things about me it never entered my mind that they were overdoing it. I mean there wasn't any way to overdo it. I WAS READY! It was hard though, 'cause people had me all over the place, but they had never seen me or heard my music.

'Reaction was great just about everywhere. California was kinda hard, we had to play there about three times before they liked us. In those days you were supposed to be anti-superstar, and I had played there before I made it, at the Fillmore on audition night, and people went crazy. But when I came back as a 'star' folks were ready to hate, and they did. We had these crazy people working for us, one guy who had worked for the Dead for awhile, and he convinced us that we needed this wall of amps, I mean A WALL, like about twenty twins on each side of the stage. The Fillmore was such a little place and it was so loud that you couldn't even hear the drummer. It was just a disaster. Lonnie Mack came on after us with just one little tiny amp and wiped us out completely. We fired that roadie the next day.

'It took about two years till we really got accepted and it was really important to me, 'cause I didn't want to be a big joke, like another Ultimate Spinach, so I guess that I worked harder than I might have had I been making it slowly. I was lucky 'cause I really didn't take it too seriously. I figured that the money didn't have all that much to do with it, I mean I wouldn't have taken the money if I didn't think I could make it back. But record companies a lot of the time won't work on you that hard if they don't have that much invested in you, so I knew that they'd be working their asses off doing publicity and making sure my record was distributed so they'd be sure to get their investment back. It was more security than anything else.'

I mentioned that I thought the late sixties blues revival probably helped a lot in his early success and Johnny agreed. 'I tell you, if we came in doing' the same thing now, I don't think people would even listen to us. It was a matter of being in the right place at the right time with the right thing that people wanted to hear. I really wanted to be successful. I mean I put out every kind of record imaginable, from early fifties stuff to R&B to big bands, but blues was really my favorite kind of music and I felt that I could do my best playing blues.'

As Johnny made it though, it was clear that he was as much a rocker as a bluesman, and as he stretched out his repertoire more, problems arose that brought about the breakup of his original band. 'The trouble was that that band was a blues band, and they couldn't play rock 'n roll too well. That's the main reason the band broke up - people really expected us to be like Cream or like Hendrix's band, but it was more like James Cotton or Muddy Waters . Even thought it was real loud and had a lot of energy, it was very rough and sloppy and bluesy, and that's the way we wanted it to be. I think what was wanted was a British variation blues style and we were into more raw, country blues. Eventually the bass player and drummer were getting so much criticism that it was just flipping them out. But no matter what people say, I think they were a good blues band. It's hard to do a good job when not everybody's on your side.'

After the breakup, Steve Paul, Johnny's manager, brought Johnny together with another band he was managing, the McCoys, who has come just about to the end of the line as a band and were desperately in search of somebody or something to save their careers. The McCoys had been doing a lot of interesting music on their last two albums but had fallen from the public eye, and Paul thought that they might be able to meet Johnny's expectations as his new band.

'Johnny Winter and...' as the group was called, brought out a whole new facet of Johnny's musical personality, with the emphasis on hard rock. Their second album, a live one, brought them to the top of the performing field, and there was a new and inspired frenzy to Johnny's playing and signing. The band toured incessantly, and as vacation time always seemed farther and farther away, the band and Johnny started leaning on drugs to keep them going.

'When we first got together, I thought they were nice little healthy kids,' Johnny recalls, 'but I soon found out that they were completely insane people. Right after we had formed the band, they took me out on a walk across a stretch of the Hudson River that had frozen over. I just knew that I was gonna fall in, and sure enough, I did, and it was so cold out that steam came up from the water when I came out and Bobby Peterson (the McCoys' organ player) saw this and decided that I was God. He started following me around for a week trying to be saved and then he came up with the idea that he was Judas and walked around with a rope around his neck. He was so dinged out he couldn't dress or eat or anything. Finally he tried to hang himself but the rope broke and he wound up in the hospital and left the group. Then Randy Z, Rick's brother and our drummer, took about 60 downs one night, just to see if he was mortal or not, and he had to leave the band, too. I don't know how Rick (Derringer) managed to do it but he stayed healthy through all of this craziness.

'All the touring and lack of rest was really getting to me, and I started using heroin, and the group was going in a different direction that I didn't like, a little too teenybopperish, and it seemed that my whole life was falling apart, so I dissolved the group and put myself in the hospital.' The nine months away from the rock scene gave Johnny a chance to sort things out and try to figure out what direction he wanted his life to take.

'I really could have left anytime I wanted. I wasn't like I was locked up or anything like that. I was OK after three months, but I wanted to graduate, I didn't want to say 'I think I can leave now,' I wanted them to tell me that they thought I could leave. I was really tired of being a rock 'n roll star, as a jukebox, and I was tired of the road. I knew that I wasn't going to continue my life the way that I had been living it. For three years I had never really had any time off. It was boring, it was lonesome, it was everything horrible you could think of. I was always trying to know people, and it just didn't work. There was a wall between me and others. If I went someplace, all I could do was say hello and sign a few autographs and it really scared me.

'I knew that if I wanted to stay alive, that I'd have to keep playing, but I also knew that I'd have to rearrange my life. It's a lot easier now. Edgar and I use the same road crews, so when he goes out, I stay home, and vice versa. Also, I can now keep my music and my private life apart, and that's really very important.'

Johnny's 'comeback' has been going quite well ('I still draw the craziest audiences of anybody I know'), and he's been able to show off more of his many different sides than ever before. 'With my first band, if I did anything except blues, people wouldn't want to hear it. Then I was doing really hard rock, and that's all they wanted to hear. Now I'm able to do a little bit of everything and have it accepted as ME. I hope folks like the new album (Saints and Sinners), 'cause it opens up a lot of different areas. I'll still get guys in the audience yelling 'Jumpin' Jack Flash' or 'Johnny B. Goode' during slower songs, but I think with time that I'll be able to do everything I want to do.'

It is significant that Johnny Winter now sees time as being on his side, time to do the things that he wants to do. He no longer has to fight to stay on top. He is residing in that very special place where success is a reward for deeds well done. And judging by his two recent albums and the impressive crowds he's been drawing since his return to the tour circuit, it looks like those deeds will continue to be rewarded for a long time to come. And that's how it should be for a star of Johnny Winter's magnitude.