By William Thomas

---

Can it be that inside every skinny albino, there's a red-blooded Mississippi boy trying to get out?

Case in point: Johnny Winter.

As blues buffs know by now, Winter—the Weirdo—emerged suddenly this year when he signed a $600,000 recording contract and began to be hailed nationally as the hottest musical discovery in the land. (Time called him "the six-string super freak." One British magazine even referred to him as the "great white hope of the blues.")

What most people didn't know was that the 25-year-old peroxide albino had been fighting for 10 years to reveal himself as one of the new messiahs of the blues.

In one of those strange new twists of fate, only now does Johnny have a persona that places that kind of bite on his music, so heavy it's devastating, so destructive that only the new young can hear it.

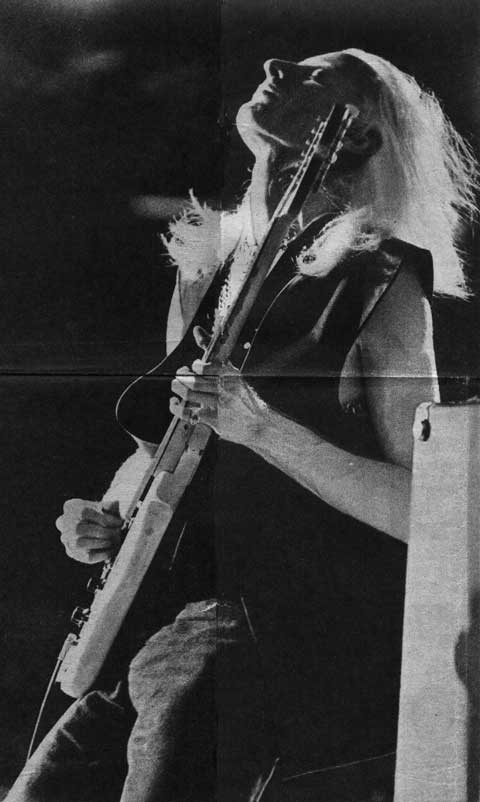

Outwardly, Winter still looks like a dissipated skeleton, his albino flesh a ghostly white. His skin, the color of paste, his white hair standing nearly straight out like an electric shock job. He has the build of a musician not making any waves outside the bandstand, but inwardly…

He has the hunger of a kid from Mississippi who got wind of things never done before and never forgot.

Recently, he holed up in the now wrinkled suites in the Holiday Inn Rivermont, overlooking Beale Street and the water which the blues around Memphis were born in. As he talked about the burden of revealing himself and his struggles to find the blues inside him, you got the impression that behind the shades (which he wore to cover his red eyes) and the white whiskers on his bones he has had a long time of performing.

He drew first color in Mississippi and had been reared in the blues there until the age of 12, yet he'd never made a real life in blues until now, earning it by playing in low-rent joints for blues guitarists and singers who only needed a good sideman and stealing up to $7,500 for a guest performance.

"My folks were living in Leland, Miss., when I came along," he began. "But before that they weren't much, hopping in Leland. They went to Beaumont, Texas, before me, and I came back to Leland, where Daddy had little cotton business. Daddy wanted me to go into cotton business, but he had no ideas about what Beale's magic could do.

"My folks were there in time to save what was left of the place up until I was 11 or 12 years old, people say, and when I started finding it out I remember it. I've wandered since then, I played in Leland, Texas up to Beaumont, back in Leland. I learned how to hum and walk."

It was never explained why he loved the blues more than Southern gospel or Texas country music, except that he was born in Leland where all the rules of cotton and country apply, and they were able to listen to blues, and rhythm and work behind cotton, so he turned out that way. Leland, they say, is one of the areas in the state where such a myth is one of the myths of the blues.

---

Leaving Texas , leading up to Beale , some story went through like,

I came along, so went along, where I grew down, and Beaumont or Leland, you have to tell me all this, or remember:

Johnny Winter is where all men know, then we started.

---

Well, Daddy played sax and sang in a barber quartet, never got anywhere but hit him for some haircuts. His wife plays guitar and sings in a church down on Beaumont, Winter keeps playing the guitar in something way different, yet it’s always another story, it all works and he tells the way of listening before you start where he played first.

But that’s all gone the moment it happened. Daddy

to stop it; he happened. He played the piano a little, and he taught me.

'Being an albino made it a little hard. But it never really was a hang-up.'

the ukulele, because my hands were still too small for anything else. Later on, when I was 11 or 12 and my hands were bigger, I started on a guitar that was handed down from my grandpa.

It was about that time that I heard the first blues on the radio. It really turned me on. I’d never heard that kind of music—they still called it race music then, and it was all coming out of Memphis and Nashville.

I loved the blues and I loved the guitar, and suddenly I was fanatic on both. Every blues record that came out, I bought. I don’t mean most of them, I mean all of them—Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Lazy Lester, B. B. King, Muddy Waters, Slim Harpo, Little Junior Parker—man, I could go on forever. I’ve got records by the thousands, and I learned to play from those. I don’t know how lessons are, but everything else I learned from those records.

'NEVER LEARNED to read music,' but that wasn’t because of the bad eyes. I just didn’t want to play notes someone else had written out. That takes it all out of it. The blues is very emotional music, man, and it’s so personal that if you get a big sound, it’s 100 percent like a song is really yours. And the more personal music becomes, the more it makes you feel good to sing about it and to hear others sing about it. Nothing makes me feel as good as playing the blues.

Anyway, we put out a record in Memphis when I was about 13. I had a band with a guy named Edgar who played drums and sax. I’m not saying that record was much because it wasn’t. But it gave me an idea of what it was like and what I could do with music.

After that I went through some studios in Beaumont and started doing pop stuff and some other commercial things.

I was glad to be working, but I was also real unhappy because that wasn’t what I wanted to be doing. So I just kept on hanging in there until I could figure out some other way to make a living.

'We played country, everything I could think of. I’d say: Well, we’ll play anything if you’ll give us a job.'

Then when I was about 15 or 16 we decided we’d had enough of that kind of music. I just started doing my own thing, and that’s what I’ve stayed on ever since.

By the time I finished high school I guess I’d learned to sing and shout a few things.

I got a band together and we started gigging around on weekends and such. We played country, rockabilly, anything we could think of, and got as many jobs as we could get. We figured we could make the guitar sound like a dobro, so we would play country, blues, or anything they wanted.

We started this band when I was 15—we called ourselves Johnny and the Jammers—and we played for school things and for beer joints and we’d get $8 a night for gigs around the state line in Louisiana. The band even put out a record and it sold 250 copies and got to No. 8 on the Beaumont station. This was before there was such a thing as FM, and we were pretty happy about that.

'AFTER HIGH SCHOOL,' I went to Lamar Tech for a semester. But I wasn’t interested in that sort of thing, so I dropped out and went full-time into music. It was a big hassle and my family got all bent out of shape, but it was the only thing I could do.

So I got a regular day job working for an insurance company—typed all morning and played at night. I worked from 8:30 to 5 o’clock, then I’d rush home and grab my guitar and run out to play until 2 a.m. the next morning. I couldn’t cut it. I was going to die off that job, man, so I just finally quit.

After that I was in Chicago about six months, and things didn’t happen. I ran out of money and came home. Then I went back up North and James Perkins, Bill Josea and Eddie Macon started a group and we did a gig supporting Arnie Avalon in Chicago, and things started picking up. So I stayed there for about six months working with the group up North. We did a lot of things in Chicago before Eddie Macon took his band out on the road to North Side and took me with him.

The only trouble we had was with a guy named Mike Pickle. Mike booked people nobody else would touch.

After that I became tired of the music and picked a guy named Beaumonte. He was kind of an oddball. Beaumonte had a little house with a bunch of musicians that were traveling through in Beaumont. But the guys would hang around his house until he found them a gig.

He was cheap, though, and would keep whatever they would make, give them sandwiches and apples, and send them on their way whenever the sandwiches ran out.

Beaumonte would put the guys on the road, put them up in some bandstands, but they were very talented.

We called the group Johnny Winter and the Blues Mafia. I could get back on my feet through the festival circuit. I’d have gigs such as The Frost. I had a 9-married group from the South and they were all hired hands. Some of them played for three years. The longest they stayed on was two years. They all had records. We couldn’t get a rest—We would do everything we'd need to survive. There were big business breakups everywhere.

'AT FIRST, THE HAIR was kind of a joke. The Beatles came around and we thought, Wow, that’s sure strange. That’s not the way to do what I did.

'The more people resented it, the longer our hair got.'

Then, people began to resent it, and it was the usual thing in the old West for hair to be cropped to the shoulders. The more people resented it, the longer our hair got. It was my stupid act of defiance.

My hair kept getting longer and longer and I had reached the point where it literally would not be cut and I hated it. It was so hot. Club owners would not let me inside. I couldn’t play for long with long hair because it was such an issue and all anybody would say was that it was unsanitary. So, I could not get inside a club. It seemed I couldn’t play very well.

Then, I decided to have my first job. Johnny and I got together and I asked my friends if I could stay at their house. When I started to get myself together, I ran into a series of people who were afraid of long hair and just plain did not like me. So, I took my guitar and hit the road. At first, I began hitchhiking in my car around Texas with a couple of friends who were also carrying their guitars. We had our canvas. We had a little fire and had some gas money. It wasn’t that bad, but as the months went by we gradually headed for Houston, then to Boston.

We played in Houston for a year, and then I said, “Hey, I’m in Boston and I am going to see what it is like.” We were living in an old converted barn in Killeen that a guy had converted for us and did some things on his own — he’s albino, too, and the chances of that happening twice in the same family are slim — anyway, we got big and we all started living together.

"I GOT MY GROUP together, and at first I couldn’t make enough to buy gas to get out of Texas. We spent what we had for food or gas or something. This went on for a couple of months. That was in April, but by September we had a little following going. We played around Texas, some bars and some clubs, and I sent out some records to Rolling Stone magazine and some other big names. We didn’t get famous.

So, we headed to New York, and it was one of those things where you live with about five or six guys. There were eight of us living in this one room in New York, calling ourselves “The Five” because five of the guys were albinos. We made some records and eventually came across this group called ‘Second Edition’ who was an old British group with a really weird name. They were making a name for themselves. Somebody gave us a record, and we eventually came across Gibbons who was living in Boston.

We picked up Gibbons for our studio and practiced constantly, never stopping. That was when we began making money. Somebody gave us money to go to Detroit and record. Our album didn’t sell, but it did all right.

I thought I’d never see Texas again. Now, I’m still living with five guys and trying to throw it in their face. But it turns me on because they wouldn’t give me a chance. Now I’ve got my own band and am proud of the way things turned out. I’m tickled they never had me cut my hair.”

TODAY, WINTER is on easy street. He lives in a rented studio apartment, puts out records when he feels like it. He still has his long, flowing white hair and people now see it as a trademark. He does not cut his hair but keeps it. He hasn’t had a hit since ’68 but still plays the blues the way he did back then.

Winter, whose blues play is the slow and deliberate kind that makes you sweat, is back on the road now, traveling to small clubs, playing with a smaller market, but keeping the same gritty, direct sound that he started with, a sound many blues purists love.

For a long time, he had been with the same band, the bass player and drummer had been with him for years. There were hardly any personnel changes. Now that band has broken up, and it is only Johnny Winter himself.

He has been in bitter fights for a long time. He’s been ripped off and sued, sometimes in million-dollar lawsuits, sometimes for smaller amounts. He’s lost a lot of money and has a hard time paying rent, and nobody knows how to reach him.

But his life isn’t bitter. After all, he's Johnny Winter and can still look in the mirror and say, ‘Hey, I’m albino. At least I know what I am. And my hair? At least I don’t have to worry about that.