A Texas albino called Johnny Winter wows the pop world with music that is old, new, borrowed—and blue

It was the most dramatic, most stoned Monopoly game I've ever seen. The setting was the dining room of a comfortable remodeled stable on an estate near Staatsburg, N.Y., two hours north of New York City. Sunday evening supper had been cleared. The lights shone through glass doors on banks of snow outside.

Park Place, Boardwalk, the yellow and orange properties, and the railroads belonged to Steve Paul, impresario of The Scene nightclub in New York and recent discoverer of Johnny Winter, a Texas guitar player being hailed from Variety to Cash Box as rock music’s next superstar. Steve had hotels everywhere and openly goaded other players to quit.

Across the table sat Winter, a light (5'11", 130 lbs.) but wiry albino, squinting at three green property titles and muttering about being tired of losing to Steve all week. With all his cash, Johnny bought houses—and very quickly, fate smiled: in rapid succession, Steve landed on Pacific, Pennsylvania, and Pacific, stumbling in a flurry of mortgages.

“Never thought it could happen,” said Steve.

A week later, I had trouble believing what happened in the real world. Clive Davis, the cherubic 37-year-old president of Columbia Records, arrived with supporting staff. On a bed in a converted upstairs loft, he and Johnny Winter signed the largest recording contract ever offered by Columbia to a new artist—a $100,000-a-year guarantee for three years. (Bobby Dylan initially signed for nothing, as did Simon and Garfunkel.)

The money was not for Johnny’s guitar virtuosity alone, or just a bet on an instant legend. It was a reward for hitting New York in time for the Blues Revival.

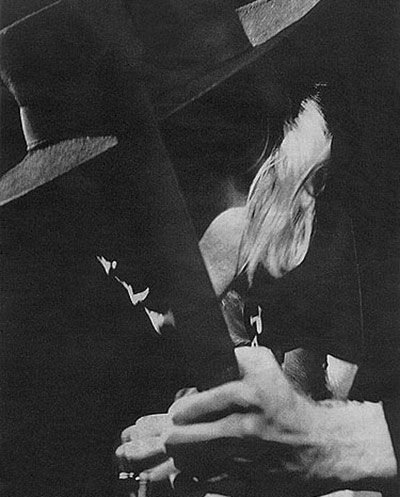

Nights of rehearsing,

Monopoly, and waiting...

punctuated by frenetic

bolts into the city.

The success scenario, briefly: Late last year, music critics began writing of public distaste for complex, freaked-out rock and a fresh interest in the wellspring of pure blues. Steve Paul, 28, who doesn’t know much about music but a lot about people and trends (he had booked Muddy Waters and other bluesmen at The Scene two years earlier), read a paragraph in "Rolling Stone" magazine about a "cross-eyed albino" who was one of the world’s best white blues guitarists. Equipped with a toothbrush, Paul flew to Texas, found Johnny Winter in Houston, and suggested he come to New York “to meet people and look around.”

After much back-and-forth (Steve: “He thought I was crazy, I guess, until I sent a free round-trip airline ticket a week later.” Johnny: “I was prejudiced against him—he talked too much, and I told him I didn’t want a manager.”), Johnny arrived in New York on December 13. Steve engineered a 15-minute jam session at the Fillmore East. The rest can only be described as media and word-of-mouth hysteria, New York-style.

I met the whiter-than-white hope of the record industry when he returned from Houston in January, accompanied this time by his girlfriend, Carol Zurga (or Roma???), a tall redhead, and his two sidemen, drummer "Uncle" John Turner...

Johnny Winter’s Band and Life on the Road

Johnny Winter, 24, and bass player Tommy Shannon, 22, along with their crew, spent many months together in cramped quarters. Short, full-bearded Uncle John, from Port Arthur, and shy, lanky Tommy from Dumas, had mostly slept on the floor of Johnny's apartment since April. One of their final gigs in Texas had been a debutante dance at the Houston Country Club, which says something about the state’s tolerance for deep, funky blues.

The next few weeks were spent in a kind of tense seclusion at the country house rented by their manager, Paul, who had won Johnny’s confidence. “We got standing ovations in San Francisco last fall,” Johnny said, “but no one set up all the press and exposure like Steve did here.”

Nights were filled with rehearsals, Monopoly games, and waiting, which blended into days of sleep, occasionally interrupted by frantic trips into the city for concerts at the Fillmore, a weekend at the Plaza Hotel, shopping tours, and contract discussions.

“I’ve never been cooped up like this,” Johnny complained mildly one night. “Playing a joint every night is peace and happiness to me.”

Money was carefully budgeted, as the Texans were living on funds loaned to Steve by friends. “Keeping a pure lifestyle is all that counts,” said Steve, who claimed record company bids of up to $500,000. “The Establishment wants Johnny. It’s just a matter of how, where, and when we'll get together.”

A man said: “It’s some freak who uses hair coloring.”

Johnny Winter was happy the week after signing his contract. It wasn’t the money. It could have been Monopoly money for all the excitement shown by him and Steve, with whom he had yet to sign a management contract. Johnny was happy because Clive Davis of Columbia had told him he would have complete control over the music on his albums and over himself.

“That’s the only thing I don’t like about becoming well known,” said Johnny. “If you can’t live the way you want.”

The next weekend, he and his group went to Boston, where they had equal billing in a concert with Janis Joplin, whom Johnny knew from Texas: she had grown up in Port Arthur, near Beaumont. It was the weekend of the big 20-inch snowstorm, and the truck carrying all their equipment didn’t arrive until five minutes before the show. Johnny went on wearing only...

"a black-leather vest over his shoulders (“It'll be cold, but I'll be so beautiful it won't make any difference”). The young audience, who had come for Janis, responded lukewarmly. During intermission, I heard a man comment: “It's some freak who uses hair coloring.” On the way back to the hotel, where a Negro guard almost refused to let him enter, a group of rather greasy hippies screamed epithets at Johnny. “Man,” he said, “you know you're cool when even hippies yell at you.”

Rock musicians are always stared at and rejected in hotels and restaurants. Johnny has been stared at and rejected all his life. His music—the black man’s blues—expresses the anguish, the resentment, sometimes even the absurd humor, of a pigmentation disparity beyond anyone’s control. Besides having pure white skin and hair, Johnny lacks full coloring in his irises and was born astigmatic. His vision is 20-200 (“I use one eye mostly, the other tends to groove around where it wants”): he sees the shapes of things but has trouble with detail over 30 feet. The way his eyes rove around and fail to focus often makes people uneasy. Uncle John Turner likes to describe the numerous..."

"occasions in Texas lounges and beer joints when Johnny lost his temper and absolutely terrified people who made fun of him—“there’s nothing quite like a crazed albino.” At most times, with his slight overbite, Johnny looks like a cheerful mole.

The pain of being different began in schools in Leland, Miss., where Johnny lived as a boy, and in Beaumont. His dark-haired parents provided comfortable homes in both places, with a lot of love and a lot of music.

“I was singing as soon as I could talk.” But in school, it was embarrassing. “When the teacher would put something on the blackboard, I’d go up real quiet and ask if I could have a copy at my desk, cause I couldn't see. But she’d make me get a chair and sit up real close, in everybody's way. It was a drag, you know, because I was just a little kid and pretty sensitive. Later, in high school, I couldn't drive a car when everyone else did or play sports. By then, I was getting into music and didn’t care.”

Insults by adult Texans continued to rankle, but Johnny is philosophical: “It used to piss me off when people were so stupid and cruel to call me a fag or a girl, even when my hair..."

was short. But now it’s more like an ironic joke than a bitter feeling. In fact, I kinda *enjoy* seeing normal people freak out over me. It wrecks most of ‘em so bad they just can’t handle it—*can’t figure out what I am or why I’m there!* What Johnny feels goes into his blues, and on his Columbia album he sings of “goin’ back to Dallas ... the meanest town I know”:

You know I Ain't Evil and I'm just a-having' fun. But there is so much --- in Texas. That you're bound to step in some.

Johnny was 11 and had been playing guitar a few years when he first heard Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, the Chicago-style bluesmen, on station WLAC out of Nashville. His devotion was instant. He began buying records, listening to the radio, and spent hours a day playing by ear, teaching himself. He went from B.B. King and Bobby Blue Bland to Lightnin’ Hopkins and back to the primitive Delta masters, Charlie Patton and Robert Johnson. “I loved the blues,” says Johnny, “from that time, no matter how many people hated ‘em. You can feel that nobody cares about you, and you sing, and it doesn’t make any difference and you don’t care. It’s not a happy feeling, it’s not sad. You can cry, and it’s good.”

For almost ten years, starting out with younger brother Edgar (also an albino and a first-rate musician on piano, tenor sax, drums and bass), Johnny played in various bands in Texas and across the South, doing whatever the crowd wanted—hillbilly, rock ’n’ roll, soul music, standards, light jazz—and rarely getting to play the blues. “I never liked to force my music on anyone. It was a matter of waiting for an audience. I used to play sometimes in colored clubs. I felt a common bond with Negroes. Their music was my music, and they appreciated it more than whites when I played it well.”

With Turner and Shannon, Johnny formed “Winter” in April, 1968, and began to play just blues. They survived, barely. Now, they are touring major pop festivals before crowds unimaginable a year ago. “Winter” currently gets up to $10,000 a performance. Playing a three-year-old, red-and-cream Fender Mustang electric guitar, Johnny has become the peer of B.B. King and Mike Bloomfield (both heard him years ago and never forgot it) and of Jimi Hendrix, who ambles up to jam with him at The Scene. Johnny’s forte is to energize simple motifs with flashing melodic and chordal embellishment. Rock critic Mike Jahn calls him a “great blues eclecticist, he goes from rural to urban fast and smooth.”

Johnny pays himself and his sidemen $100 a week. I asked him what success meant, if anything. “I can groove on it,” he answered, “like going to the Plaza and meeting Mia Farrow. But I can’t mix me up cause I don’t have to have it. I was happy without it, and can go right back to being happy if I lose it. I’m just glad a lot of people want to hear the blues.”